Scientific thinking in the West started off sort of weird. Before the Greek philosopher Thales:

Early Greeks, and other civilizations before them, often invoked idiosyncratic explanations of natural phenomena with reference to the will of anthropomorphic gods and heroes.

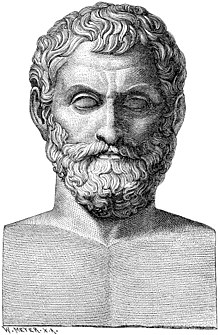

Wikipedia

This was the state of the world until Thales, back around 600BC, started to think about why stuff happens in terms of causes and effects in the physical world. He came up with 3 propositions:

- All is the moist

- The lodestone has psyche

- Everything is filled with gods

Wat. It sounds like nonsense, but if you think about it, you can imagine him meaning something like:

- Everything is made of water.

- Magnets (lodestones) have spirits as evidenced by the fact that they move things.

- Everything has an essence of gods, that dictate how each thing behaves.

All 3 of those propositions are… well, they’re wrong. But what he’s doing is novel. Rather than attributing natural phenomena to the arbitrary whims of the Gods, he’s trying to explain the world as a system where things make sense.

To us, it feels like the scientific way of thinking is just how humans naturally think. When we want to know why something is, we naturally look for a chain of events. Strangely though, it hasn’t always been this way. Thales was pioneering a new way of thinking. He was one of the first natural philosophers.

This post was directly inspired by John Vervaeke’s excellent lecture series Awakening from the Meaning Crisis. He addresses Thales in lecture four, linked here.